Read more from the ACLU Archives: The Enduring History of the Civil Rights Movement.

The march from Selma-to-Montgomery, led by Martin Luther King, Jr., is an iconic and memorable moment during the Civil Rights Movement and in U.S. History, but to understand its significance in time, it is helpful to place it in context with the South's resistance to racial integration as it relates to voter suppression.

The First Steps towards Integration (1954-1957)

It is important to realize that the Supreme Court case Brown v. Board of Education happened in 1954, and Rosa Parks was arrested on the bus in 1955--a full 10 years before Bloody Sunday and the Voting Rights Act. A month after Parks' arrest, governors in Georgia, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia vowed to block school integration, and the Virginia legislature passed a resolution on February 1, 1956 that the Brown ruling was "illegal encroachment" on states' rights. In fact, the entire Congressional delegations from Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, and Virginia submitted their "Southern Manifesto" to oppose school integration.

A year later on February 8, 1957, the Georgia Senate also voted that the 14th and 15th Amendments (guaranteeing equal protections and the right to vote for Black people) were null and void in the state. Less than a week later, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) was formed, with Martin Luther King as its chairman.

The Shift towards Voting Rights (1958-1964)

In 1957, the first Voting Rights Act was passed and signed by President Eisenhower. It was meant to show federal support for desegregation and to ensure that all people could exercise their right to vote; it also established the Commission on Civil Rights, which investigates and makes recommendations regarding civil rights issues in the U.S. However, this had only a marginal impact on Black voting.

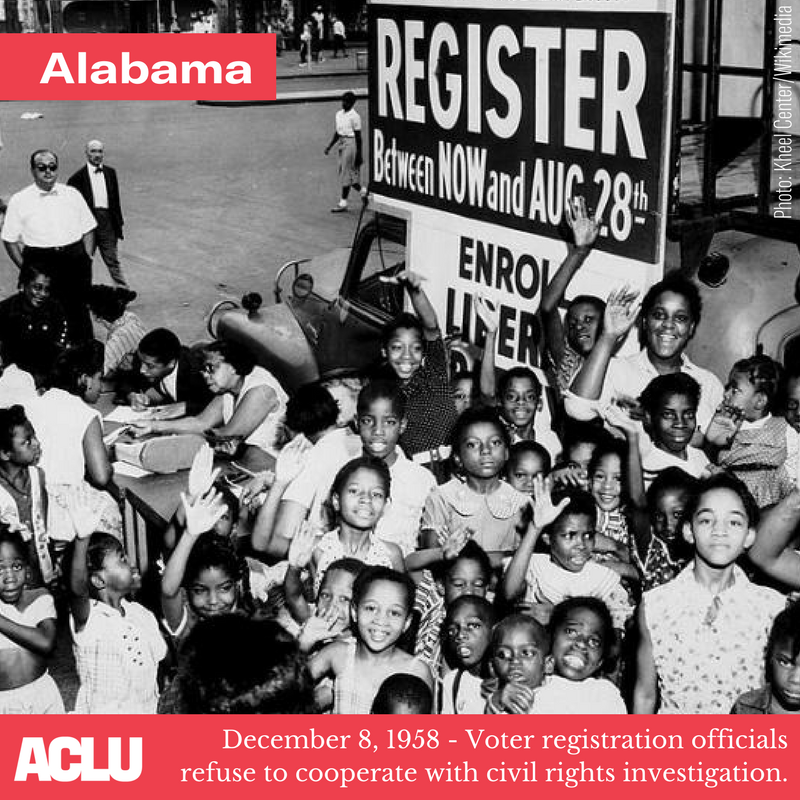

When the U.S. Civil Rights Commission came to Alabama in 1958 to investigate charges of voter suppression, registration officials refused to cooperate. George Wallace, who was Circuit Judge at the time and who would later infamously stand in the University of Alabama school door to bar Black students from enrolling, ordered the voter registration records be impounded, threatening "I will jail any Civil Rights Commission agent who attempts to get the records."

Meanwhile, throughout these years, voting rights activists like Herbert Lee (voter registration activist in Mississippi) were frequently targeted and killed. Churches that were used for voter registration drives and rallies were bombed. Two Black churches that were frequently used for Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) activities were burned in Sasser, Georgia in 1962. The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing that killed four girls in Birmingham happened in 1963.

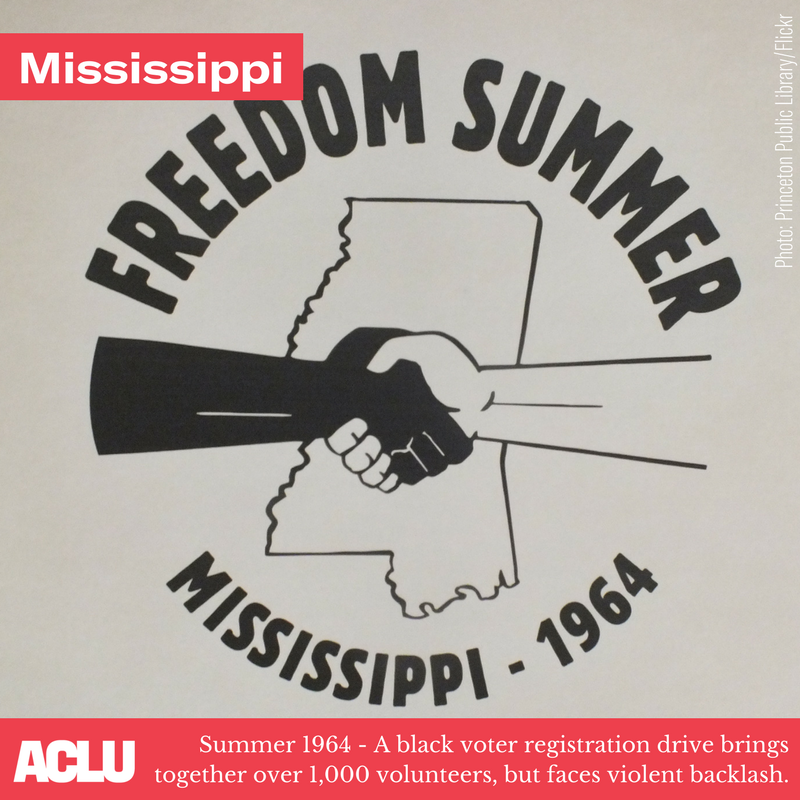

However, grassroots organizations like SNCC, SCLC, and others were busy running voter education and registration drives. During the 1964 Freedom Summer, over 1000 volunteers came to Mississippi to register and train others. While the campaign was met with violence and intimidation including KKK abductions and murders, it received national news media attention, and connected activists who were able to use what they learned in their own communities. It would be these organizations, engaged activists and citizens that would set the foundation for the historical march the following year.

The Events in Selma

After several years of resistance to voter registration activities by local law enforcement in Selma and surrounding communities of Dallas County, Martin Luther King, Jr. and SCLC held several demonstrations at the Dallas County Courthouse. On February 17, 1965, voting activist Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed by an Alabama state trooper. His death nine days later outraged the Black community, and his fellow activist James Bevel called for a protest march from Selma to Montgomery to speak with Governor George Wallace about Jackson's death.

When the protesters arrived on Sunday, March 7, Bevel, along with other activists like John Lewis and Amelia Boynton, led six hundred marchers across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. At the other end of the bridge, Alabama State troopers and local police formed a blockade and ordered them to turn around. Upon refusal to do so, the officers attacked the protesters with teargas and billy clubs, sending over fifty people to the hospital. This day is now known as "Bloody Sunday."

Video: CNN looks back on the Selma marches

Two days later, a crowd assembled with King for a second march. To avoid the violence that had happened on Bloody Sunday, SCLC applied for a court order to prohibit police interference, but instead, the federal court ordered a temporary restraining order, prohibiting the march until he could review the case more. King obeyed the order, and the crowd of marchers turned around at the bridge and went back to Brown Chapel.

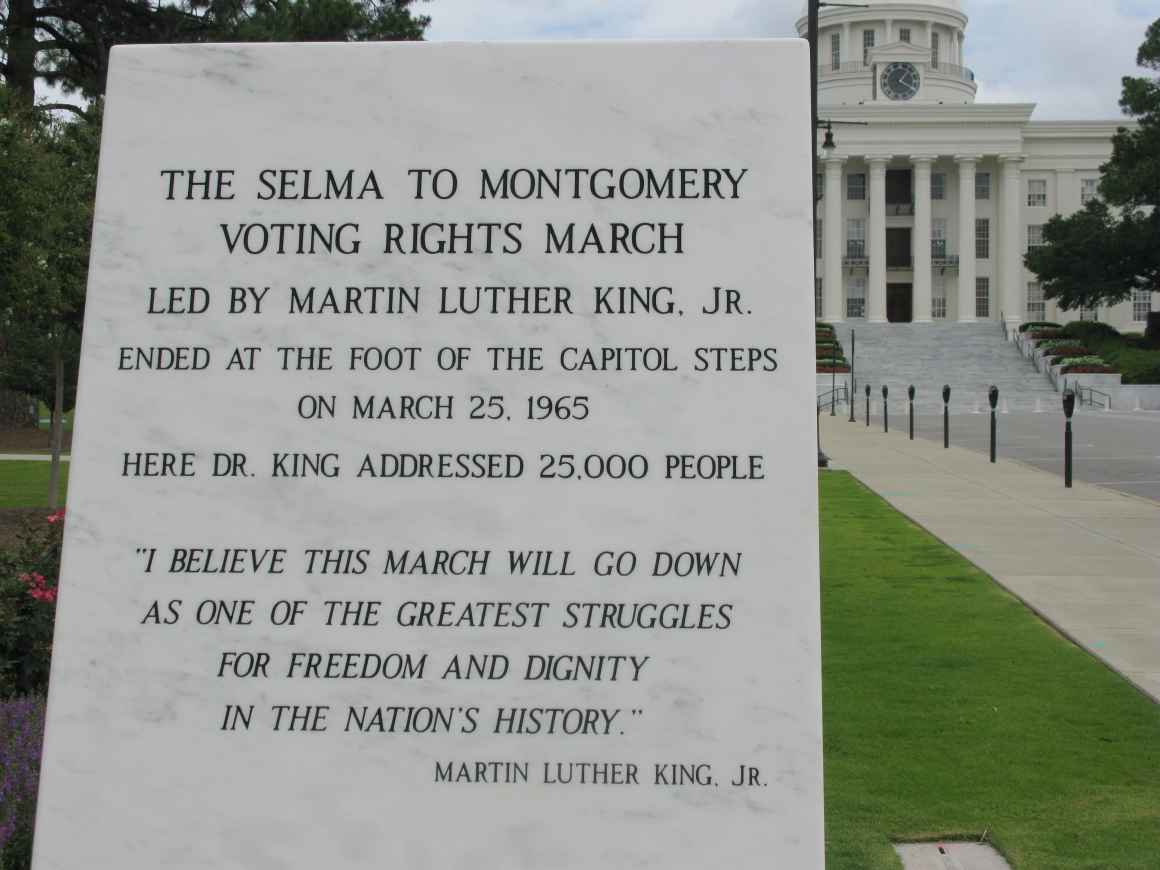

Finally, on March 17, the federal judge ruled in favor of protesters' right to march without interference from the state, and on March 21, almost 8,000 people gathered at the Selma church to march to Montgomery. Because of the width of the highways at the time, only 300 people were permitted to continue marching through Lowndes County, but once they reached Montgomery County, more marchers rejoined them so that roughly 25,000 people arrived at the steps of the Capitol on March 25. Those that walked the entire stretch would have walked approximately 54 miles in the cold and rain, through hostile territories of mostly white, rural communities.

The Aftermath

These marches provided a national and needed spotlight on civil rights and racial discrimination in the Deep South. Because of the widely viewed footage and photographs of the brutality on "Bloody Sunday," audiences all over the world were able to see the terrorizing of Black people, and King's speech at the Capitol received attention for the marchers' message. This crucial activism paved the way for the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which passed just a few months later to enforce voting rights guaranteed in the 15th Amendment. Nevertheless, Alabama held onto its poll tax in state elections until 1966, when federal courts declared them unconstitutional.

Photo: Monument to the Selma-to-Montgomery march on Dexter Avenue in Montgomery, Alabama

While this has been an important piece of legislation that has prohibited states like Alabama from implementing Jim Crow laws and other forms of racial discrimination, it was undermined in 2013 when the U.S. Supreme Court eliminated federal oversight in state election laws. Since then, we have seen a new wave of legislation like voter ID laws that are disenfranchising voters of color across the state and leading to legal challenges, which goes to show that the fight for civil rights and civil liberties is never-ending.

Cover Photo: Marchers carrying banner "We March with Selma" in Harlem; Source: Library of Congress

See more photos of the Selma marchers at the Alabama Archives and from the Steven Kasher Gallery via CBS News.